This year I have been part of the TPDL Teacher Professional Development Languages Course. It’s been a really great and challenging experience, and for our final assessment, we had to complete a learning inquiry looking at the way task-based language teaching affects an aspect of learning in our language class. Here’s mine:

Introduction

Teaching as Inquiry is an important concept in the New Zealand Curriculum (2007). Serving to improve both teacher professional learning and student outcoomes, the process involves enquiring into an aspect of your own teaching practice, focusing in particular on the strategies used to unlock learning for students.

This teaching inquiry report links task-based language teaching (TBLT) with New Zealand Curriculum’s key competencies, exploring the relationship between the two, and how this in turn supports student engagement in my German classroom.

As both a classroom teacher at an intermediate, and a language teacher I am exposed to a range of different pedagogies. As task-based language teaching has become part of my pedagogical practice in teaching German this year, so too has my focus as a classroom teacher changed to centre increasingly on the salience of dispositional thinking and learning, and the role of ‘key competencies’ in supporting students’ learning. Both are fast becoming passions of mine, so naturally I wanted to see if I could combine these two things, which are working so well individually and investigate how they play into each other.

Literature Review

Task-based language teaching (TBLT) is a pedagogical practice, which has evolved from more traditional models of language teaching and learning. Language teaching has traditionally followed what we might call the PPP model – present, practice, produce (East, 2012). Indeed this was commonplace within New Zealand schools until recently and still continues to be used in a large number of schools today. In the 1960s, language pedagogy began to move away from this model, and started to focus on something radically different – communication (Ellis, 2009). Of course, this may seem obvious to us now looking back from the 21st century, but at the time it was a radical notion.

As the pedagogy of language learning evolved in New Zealand, new ideas came to the fore, and in the early 2000s the concept of task based language teaching started to gain popularity (East, 2012). With implementation of the new New Zealand Curriculum in 2007 and it’s being mandated in 2010, Task-Based Language Teaching quickly became the language pedagogy of choice for New Zealand teachers (East, 2012). The New Zealand Curriculum takes a communicative focus to language teaching and learning. This is reflected in the centralisation of the communication strand over language knowledge and cultural knowledge (Ministry of Education, 2007).

Task-based language teaching is essentially a way of teaching a language that focuses on communicative competence – that is learners communicating with each other successfully. It challenges the teacher to create authentic contexts for interaction, something which resonates strongly with ideas of dispositional thinking, according to Hipkins et al. (2014). TBLT calls these authentic contexts tasks and requires them to meet certain criteria to offer maximum benefit to learning. Tasks must; require interaction; have a gap of some sort that needs filling; achieve a non-linguistic outcome; require learners to choose the language they use; and be assessed by the completion of the task rather than the language use (Nunan, 2004). In essence this is problem-solving in a foreign language.

There is still little research drawing explicit links between task-based language teaching and dispositional thinking, so in the following section I have opted to highlight some of the most salient points about dispositional thinking and draw connections between these and task-based language teaching.

Dispositional thinking as pedagogy highlights the importance of and need for emphasis on cultivating the dispositions for learning as opposed to knowledge or skills (Claxton, 2008). It focuses on creating a mindset where students are open to development and learning – aptly described by Carol Dweck as a ‘growth mindset’ (2006). By emphasising dispositions, described by Guy Claxton as habits of mind that support learning (2008), we are able to create a responsive pedagogy which is future focused and learner centred. Our New Zealand curriculum uses the 5 key competencies as a vehicle for doing this (Ministry of Education, 2007). Hipkins et al. (2014) posit that dispositional thinking and emphasising the dispositions or the capabilities or competencies – whichever language you choose – through authentic tasks is the best way to build a future-focused curriculum. This idea of authenticity reflects the core values at the heart of task-based language teaching, indicating that there is considerable mutuality between the two pedagogies.

Other researchers concur, arguing that as teachers we need to be more future-focused and adaptable and as Bolstad et al. (2012) put it we need to adopt “a more complex view of knowledge, that incorporates knowing, doing and being. Alongside this we need to rethink our ideas about how learning systems are organised, resource, and supported.” This clearly has strong echoes of task-based language teaching’s shift from a more simplistic PPP model of language learning to a dynamic and complex idea of language learning as a communicative act. At the same time this emphasises the need to deepen students’ thinking, and suggests that they way we organise learning can help us to achieve this. The above quote from Bolstad et al. (2012) is also highly reflective of Ellis’ 11th principle for language teaching that indicates that there is a subjective element to teaching and learning a language which enables students to make sense of language learning in their own ways (Liddicoat & Scarino, 2013), not only ‘knowing’ a language, but also developing an understanding of what it means to ‘do’ and ‘be’ in that language.

Rationale

There are many characteristics of task-based language teaching that reflect important elements of dispositional thinking. Firstly task-based language teaching prioritises interaction – important for speaking a foreign language definitely – but also highly engaging and reflective of the way 11 – 13 year olds make sense of their world – in fact, how we all make sense of our worlds according to McDowall (2010). It places meaning at the centre – never mind whether you do it perfectly, start by trying. And, as we have already discussed it is authentic – based on problems, contexts and real world scenarios.

Task-based language teaching scaffolds students in their language, drawing on the Vygotskian theory that “knowledge is acquired primarily through social interaction and that providing a supportive environment in which interaction can occur enables children to advance to higher levels of knowledge and performance” as cited in (East, 2007, p. 32).

And perhaps most interestingly, I believe it is strongly grounded in the New Zealand Curriculum’s key competencies, which are not only an integral part of the way students learn, but also key skills in today’s fast paced, technology driven world where globalisation is a daily fact of life, as Hipkins et al. (2014) argue.

There is a part in the Learning Languages Curriculum Area Overview which reflects this notion;

“Languages link people locally and globally. They are spoken in the community, used internationally, and play a role in shaping the world. Oral, written, and visual forms of language link us to the past and give us access to new and different streams of thought and to beliefs and cultural practices… As they learn a language, students develop their understanding of the power of language. They discover new ways of learning, new ways of knowing and more about their own capabilities. Learning a language provides students with the cognitive tools and strategies to learn further languages and to increase their understanding of their own language(s) and culture(s)” (Ministry of Education, 2007 p. 24).

Rationale and Focusing Question

Learning a language is not enhanced by integrating the key competencies into teaching and learning, it requires the key competencies to be taught effectively. The key competencies are at the heart of learning a language, and the key competencies in turn provide a New Zealand framework for developing dispositional thinking in students. Both task-based language teaching and dispositional thinking are future-focused in their nature, and through my research, I have come to believe that both are vital for create a responsive curriculum and pedagogy within my language classroom.

The research I have conducted has led me to understand that task-based language teaching and dispositional thinking (via our New Zealand key competencies) are intricately interwoven, but are in essence tools – not the outcome. As an intermediate teacher, my priority in teaching a second language has always been to introduce students to the possibilities that come with learning a second language – focusing primarily on student engagement. As this is an important facet of my language teaching, I decided to use it as part of my focusing question, which is:

How do language tasks and the key competencies interact to support learner engagement in German?

Context

I have 26 learners in a composite year 7/8 class, about 50/50 male and female. My students have a range of ethnicities and cultural backgrounds and a number identify with multiple ethnicities. Almost 50% of students speak at least one other language. I have a group of dyslexic students in my class and my students work between level 2 and 5 on the curriculum with most working happily at early – mid level 4 across most curriculum areas (aside from learning languages). They are a diverse bunch of learners and while this brings some challenges for the German classroom, it’s bought a lot more opportunities. Learning a language has been a great leveller. Everyone in my class began at level one of the language learning curriculum, with no advantage over each other.

My students began the year with no choice in the matter of language learning, since they were all in my class, they were all going to learn German all year. While most students were curious (thankfully none we’re downright disinterested), engagement and interest ranged from very low to moderately high. Most of my students had little or no knowledge of German beyond the odd greeting and of course Hitler. Once we dealt with the Hitler issue, we were able to move on to the language and culture itself.

I am both my students’ classroom teacher and their language specialist teacher. My students have between 1 – 3 hours of German a fortnight depending on what else is going on in class. This is usually broken up into one or two 45-minute chunks and then little bits and pieces dotted in around the rest of the timetable. We regularly use German for greetings and other in-class formulaic language throughout the day.

Having started with the basics, we’ve now moved on to look at Essen und Kaufen in der Stadt (eating and shopping in the city). And the lesson I’m focusing on in this teacher inquiry is mid way through this unit.

Task

The focus of this lesson was threefold, give students an opportunity to practice the numbers 1 to 20, introduce German currency and talk about places for purchasing food – the Bäckerei, Flesicher, and Obstmarkt (bakery, butcher and fruit market respectively) and to introduce the new words teuer and billiger or cheaper and more expensive for comparison.

The task students were set was to purchase the items on their grocery list for as little money as possible and then calculate how much change they had left – all in German of course. In this task I aimed to bring in cross-curricular elements, particularly maths, creating links to our financial literacy topic. Five students and I (so that I could hear and free assess the students in interaction) played the role of shopkeepers. Students had to approach and ask us whether we had items and how much they cost in order to find the best shop to purchase a particular item.

The lesson began with a pre-task, brainstorming the sort of language we might use in a shop and going over some newish language that the students had only encountered once before. We then moved onto the task proper and followed up with a discussion about which was cheaper and looked at the words teuer and billiger (cheaper and more expensive) to help the students express their meanings in the target language.

Reflection on Task

From teacher observation, a range of German phrases and sentences were used:

- Guten tag!

- Hallo

- Danke

- Ja

- Nein

- Hast du…?

- Ich habe…

- Ich habe das nicht

- Was bedeutet das?

- Es ist …. Euro

- Nummer 1 – 20

A significant portion of the language was what we had discussed might be useful, however it was good to hear the students drawing on their prior knowledge of interactions with phrases like ‘guten tag’ ‘danke’ and ‘was bedeutet das?’

From teacher observations during the task, all students were speaking German most of the time and all of the time for interactions directly related to the task. Every student succeeded in completing the task, some faster than others, and most students were actively engaged in the discussion and comparison post-task.

In reflecting on this task, I sought specific data and feedback from students about their motivation and the skills they feel the use in task-based language learning. I collected this by way of independent reflection questionnaires. At my school we use Guy Claxton’s Building Learning Power framework for making the key competencies more accessible for students. Students were asked to identify which of these dispositions they used during the lesson. They were also asked about their enjoyment of German, their response to the task and given an opportunity to provide any general feedback.

The forms were anonymous and only took few minutes.

Constraints

One of the biggest constraints in my German classroom is keeping students motivated to learn when there is a high discrepancy between their cognitive level and the language level in the target language. Introducing elements of other curriculum areas, particularly maths, has been successful in managing this. Maths is an especially effective example because little vocabulary is required for students to think at a cognitive level more closely aligned to their own abilities in their first languages.

Time is also a constraint, with only 3 hours maximum a fortnight, and often less, it can be challenging to ensure that students are retaining vocabulary when they are not using it.

Within this task itself, students’ memory and knowledge of the numbers was the biggest constraint. While they could easily use and understand a range of phrases in interaction asking for the price was difficult because they were struggling to remember the numbers.

Next Steps

Feedback from the task enabled students to talk about how they found the level of the task, most feedback was encouraging and suggested that this task was at the right level, however a handful of students found the task too easy. This suggests that I need to increase the differentiation within tasks and allow opportunities for those students who are confident in their German to extend themselves.

I really liked the authenticity that creating cross-curricular links brings, however I feel this could be deepened by bringing in more of an inter-cultural element. Contrasting and discussing differences between the places we buy food in Germany would be one example.

My final next step is to focus more on form in an intercultural context. This task was a perfect opportunity for students to talk about and practice using the formal language in interaction, which we didn’t do.

Conclusions

Before beginning the analysis of this task, I knew that I needed to link the Building Learning Power language my students know with the key competencies, so I began by mapping the BLP dispositions onto the key competencies. Students were asked to identify as many or as few of these dispositions as they thought they used in their learning task. All students choose at least one and most choose 3+. As you can see here, these are spread across all 5 of the key competencies, and the specific dispositions are indicated. Being absorbed in their learning and collaborating with others were clearly the most widely used skills. Adventuring, imagining new ideas and connecting ideas together were also identified as being important for the task.

While thinking was identified as the most used key competency, managing self followed a close second, reflecting the need for a non-linguistic outcome and the importance of learner choice in language use in TBLT. This is particularly evident in the prioritisation of thinking over using language symbols and texts. This then correlates, as we shall see with a high level of engagement in the task and learning German more generally for my learners.

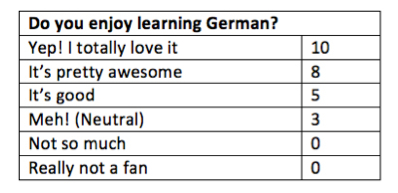

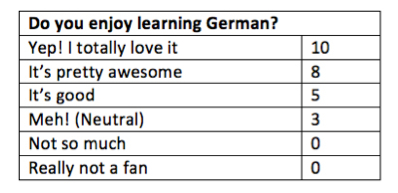

When students were asked to report their engagement in learning German on a scale from “yep! I totally love it” to “really not a fan”, all students placed themselves in the neutral to extremely highly positive band. 18 out of 26 students reported high levels of enjoyment and motivation in learning German.

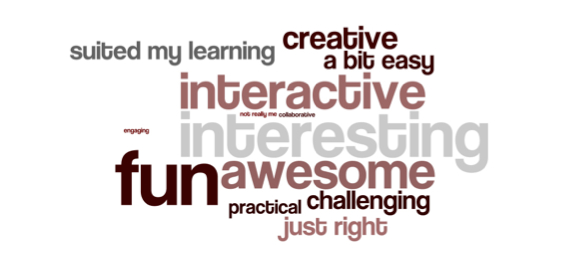

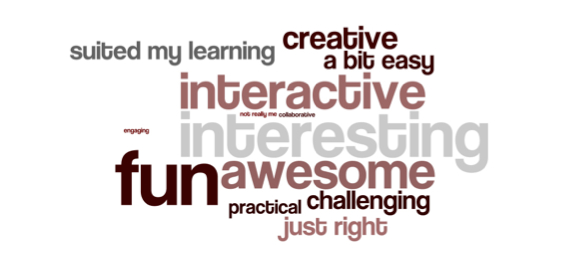

And in their own choice of words this is the students’ response to the task – the bigger the word the more people chose it.

Words like ‘fun’ ‘awesome’ ‘interesting’ and ‘interactive’ again reflect the high level of interest and engagement in the task.

It is clear to me from both my own professional reading and the data from my students that TBLT draws heavily on the key competencies whether explicitly or inadvertently – it requires students to actively be using all 5 in a holistic and authentic way. This in turn reflects a positive trend in high levels of engagement and enjoyment in language learning for my students. Students find TBLT an enjoyable and interactive way of learning, but to conclude our journey I’ll let them have the last word:

“It helps actually communicating with German in a conversation”

“It makes me think about the words that I should use in that sentence”

“I remember things better when I act it out”

“I learnt how to interact with other people while learning German. I felt I was engaging a lot more than just learning words and remembering them (which I suck at.)”

I believe it is because they are using all 5 of the key competencies in an authentic context that students are highly engaged, interacting and engaging with others while also thinking critically through German about a range of issues. After all, as one of my students put it:

“It shows me effective real life uses for my knowledge”

References

Bolstad,R. Gilbert, J., McDowall, S., Bull, A., Boyd, S., and Hipkins, R. (2012). Supporting Future Oriented Learning and Teaching – a New Zealand Perspective. Wellington New Zealand: NZCER Press. Retrieved from http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/schooling/109306

Claxton, G. L. (2008). Expanding young people’s capacity to learn. In: British Journal of Educational Studies. 55 (2), p. 115 – 134 19 p.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House

East, M. (2012). TBLT in New Zealand: Curriculum renewal. In Task-based language teaching from the teachers’ perspective. (pp. 19-47). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Ellis, R. (2009). Task-based language teaching: Sorting out the misunderstandings. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 19 (3). 221- 246

Hipkins, R., Bolstad, R., Boyd, S., and McDowall, S. (2014). Key Competencies for the Future. Wellington, New Zealand: NZCER Press

Liddicoat, A. & Scarino, A. (2013). Intercultural language teaching and learning. New York, NY: Wiley Blackwell. (Chapter 2: Languages, Cultures, and the Intercultural. pp 11-30)

McDowall, S. (2010). Lifelong Literacy: The Integration of Key Competencies and Reading. Wellington, New Zealand: NZCER Press

Minsitry of Education (2007). New Zealand Curriculum. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task Based Language Teaching. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press